Qinming Medical

In 1981, St Jude Medical divested its startup low-cost pacemaker venture to a group of East Coast investors. The new organization became Cardio Pace Medical (CPM). CPM advanced the project through FDA clearance and developed a close working relationship with the Minnesota Trade Office. Minnesota had a Sister-State alliance with China’s Shaanxi Province. CPM management pursued negotiations for a Sino-American joint venture in 1984 and 1985, and Qinming Medical Inc., Pty was incorporated in Baoji in December 1985. In the following year, the joint venture built a new factory, nominated its management team, and established a formidable Medical Advisory Board of leading cardiologists. It began producing its first pacemaker models, and from 1986 through 1990, it dominated the Chinese pacemaker market, expanded to 70 employees, and hosted international pacing symposia.

Qinming was a 51%-Chinese-owned, 49%-American-owned company. In 1990, the Chinese partner (Qinling Semiconducor Co.) began embezzling funds from Qinming’s joint venture customers. CPM insisted on relocating Qinming from remote, secluded Baoji to the cosmopolitan, provincial capital Xian. The “relevant authorities” in Baoji refused. CPM successfully pursued an undisclosed cash settlement at the Shaanxi Province government for its 49% share.

Unfortunately, the first Sino-American medical device joint venture did not survive for more than half of its 15-year term.

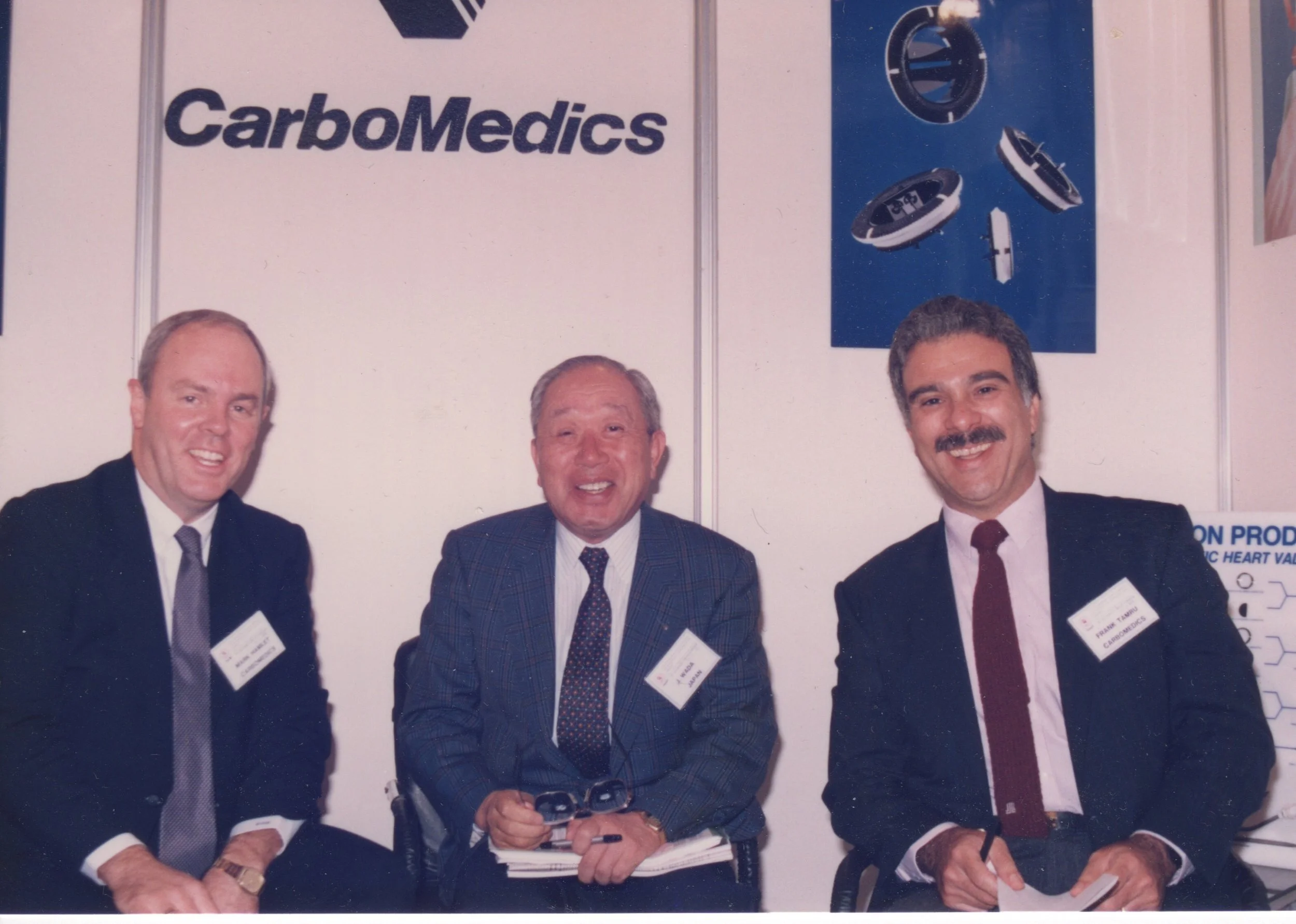

Inside Carbomedics

During my research into the origins of the Carbomedics valve and its entanglements with Manny Villafaña, Paul Stein shared a detailed account that helped untangle what truly happened between CMI, Jack Bokros, and St. Jude Medical. According to Paul, CMI’s early strategy centered on creating an inexpensive mechanical valve for the fast-growing Chinese market. The concept was initially called the PRC (People’s Republic of China) valve. Although it never reached production—Pacific Biomedical had already entered the region—it paved the way for two crucial design paths.

CMI engineers developed PRC-1, which featured a pivot system reminiscent of the St. Jude valve, and PRC-2, an open-pivot configuration. At the same time, Jack Bokros was assembling a gifted engineering team and refining pyrolytic carbon into a biocompatible, durable material that enabled more sophisticated leaflet designs. His advances lowered turbulent flow, reduced thrombogenicity, and helped establish the manufacturing precision that became CMI’s hallmark.

When St. Jude and Carbomedics later clashed in court over design similarities, CMI chose to commercialize its own valve. The PRC-1 design—legally distinct enough from SJM’s—became the CarboMedics Prosthetic Heart Valve (CPHV), while PRC-2 was shelved. Armed with a strong materials science platform and backed by Intermedics, CMI aggressively promoted the valve, and getting influential surgeons into the Carbomedics camp became a strategic imperative as CMI challenged Medtronic’s dominance in both pacing and valve technologies.

By the early 1990s, Paul explained, CMI sold the PRC-2 open-pivot concept to Manny Villafaña, who was eager to re-enter the valve market and take on his former company, St. Jude. Manny used PRC-2 as the engineering foundation for what became the ATS Open Pivot Valve. But in negotiating with CMI, he misjudged how much global traction Carbomedics had already achieved—and overcommitted. Sales targets became unrealistic, and financial strain followed, leading to Manny's eventual pushout from ATS Medical.

His departure ushered in the Michael Dale era, during which ATS renegotiated its agreement with Carbomedics and found its footing—until its eventual acquisition by Medtronic in 2010.

The Wada Dilemma

I often ran into Dr. Juro Wada when based in Tokyo for Shiley. The light-hearted but dedicated surgeon, with a mechanical valve bearing his name—the Wada-Cutter—had a good grasp of English, communicating with sarcasm, innuendo, and comedy. The Cutter valve design matched that of the early Shiley spherical-disc model, but it remained on the market only from 1967 to 1972. The model was withdrawn due to early disc-occluder wear, disc dislodgment from the valve ring, and massive thrombosis.

An influential and fascinating figure to be around, Dr. Wada performed Japan’s first heart transplant in 1968. Shockingly, he faced a murder charge by the police. At the time, Japan lacked clear legal standards for a patient to be diagnosed as “brain dead.” The donor in this case was officially declared brain dead by an attending doctor and committee, which sparked a mammoth controversy. Since the donor’s heart continued beating, it remained viable to explant and use in transplantation surgery.

This transferred its power and magnificence to a sick recipient, but a brain devoid of activity did nothing for the donor’s viability. I wondered: Why not harvest the power of a beating heart to save a sick individual’s life?

This pioneering heart surgeon kept his patients alive and deserved the label of “hero,” not “murderer.”

The Palm Reader

Years earlier, long before Jackie and I met, a Thai palmist named Sombat traced the lines of my hand beneath the faint yellow glow of a single bulb. His finger followed my lifeline as if charting a river.

“You will marry before forty,” he said softly, “and grow rich soon after.”

He got the first part right. The second took its time—though I did win a few thousand dollars on a Super Bowl bet, which he might have counted as partial credit.

When I returned to Bangkok in 1989, curiosity led me back to his small shop. Sombat examined my palm with the same steady focus, his brow furrowing as he leaned closer. Finally, he looked up with something like regret.

“You will eventually separate from someone you love,” he murmured, “but you will keep your purpose.”

I stepped back into the street, the smell of incense giving way to exhaust and frying noodles. The city roared, but his words stayed quiet inside me.

He read my future in lines of fate; Asia would teach me the rest in gestures.