Taylor’s Visits

Any thought of a defeat in the growing war with other heart valve manufacturers had not yet pierced my thinking. Despite holding the VP title and being responsible for a large area of Europe and the Middle East, I had little power to wield.

Alistair Taylor ran the division as Pfizer’s Managing Director for the Shiley product group, partly from his base in the U.K. He avoided hospital settings throughout Europe, where customers demanded answers. As an absentee leader nicknamed “The Phantom” by those in our office, Taylor addressed internal corporate skirmishes over cocktails and extended lunches, befitting the British and European styles.

We adjusted our schedules to accommodate his known appearances at the Brussels office, which typically took place from noon on Tuesdays to 2 pm on Thursdays. Side trips to Switzerland had priority for Taylor, due to his affection for Heliane Canepa, the manager of Schneider, a new angioplasty catheter-based technology company Shiley had acquired. Telephone calls and back-and-forth telex transmissions could not compete with face-to-face consults with our elusive boss. Mr. Taylor’s persistence in bringing Schneider into the Pfizer-Shiley fold shielded him from scrutiny from higher-level executives.

The Japanese Way

Gary Makowski shared a Pfizer manual on how to handle bad press during product crises—polished lines about avoiding fault and showing regret. According to Gary, that approach “would have been a disaster.” He went on to tell me about his own experiences there; the manual was not only useless for the occasion in Japan, but would have been counter-productive if followed completely, and probably upset everyone. It’s a typical Western (particularly American) canned response material of:

“Avoid saying sorry, and make sure you don’t offer anything that could make it look like the company’s at fault or that might admit culpability in any way. But you regret any inconvenience that may or may not have occurred… or something to that effect.

Gary, whom I had hired a year earlier, went on to say, “My one assignment came when Senko asked me to face a grieving family after a fatal strut failure. They drilled me like a wind-up doll: bow, apologize, bow again. I did exactly as told, heart pounding, and somehow it worked. No lawsuits, no headlines—just a quiet closure, done the Japanese way.”

There’s no way I could have done what Gary did.

Healthcare Realities- Warfarin

By the 1980s, a prosthetic heart valve had become the most expensive implantable device in cardiovascular surgery. In developing markets like India and Pakistan, patients often purchased equipment from local dealers, relying on government support if the surgery took place at a public hospital. Even then, the heart valve and bypass circuit were prohibitively expensive for the average family.

In poorer markets, long-term Warfarin therapy often slipped beyond a family’s reach. Some patients stopped taking the blood-thinning agent after the first year, convinced their health had recovered, only to suffer sudden, sometimes fatal consequences.

The lesson hit hard: even the most promising innovation held little value when the aftercare could not be sustained. With so little follow-up in many countries, the actual death toll from fractured valves may never be known. And yet, most patients remained loyal to their surgeons—proof, in my opinion, that the Hippocratic Oath endured where the industry faltered. In a business built on trust, admitting what you didn’t know was sometimes the most honest act of all.

John McKenna Regarding

Dr. Ionescu

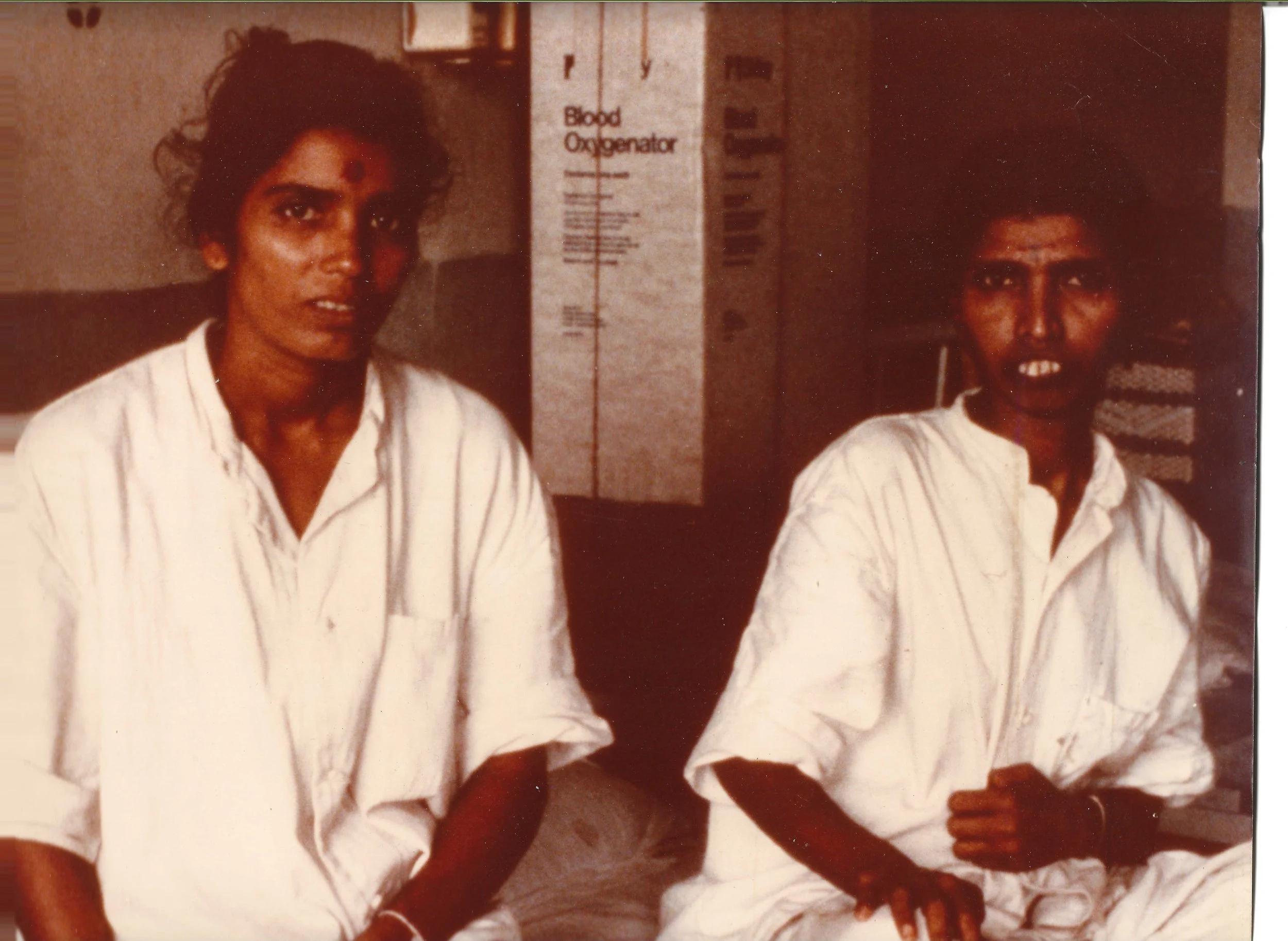

Since John had worked closely with him, McKenna shared his thoughts below later in our growing friendship. He’s pictured with Iain Maclean, Shiley’s representative in the Middle East.

"I had the privilege of serving as Mr. Ionescu’s product director for prosthetic heart valves while employed by Shiley, latterly by Pfizer Hospital Products Group, in the 1980s. Marian created the pericardial valve in the early seventies, for which millions owe their lives. When I started in 1980, he educated me not only in cardiac surgery but in the myriad of interests he had, although his enduring love was mountains and climbing them. His journey, even his escape to the UK with the assistance of Mr. Geoffrey Wooler, is a fascinating story. He had an extraordinary work ethic in Leeds and almost inhuman energy reserves, seemingly with little sustenance. That amazed me. At times, he could be exasperating and volcanic, followed by sweetness and levity; most of this behavior expressed his incomprehension about why others could not follow his quixotic mind and genius-level intellect. The most remarkable man I ever encountered.”

A Change in Technique

The cardiologists could not be forgotten as their days of dominance lay ahead. A shift in the power dynamics between heart surgeons and physicians began to rest on new developments in catheter technology. The catchy use of letters, such as in the “PTCA” procedure, began entering everyday folks' vocabulary, and for a good reason. Why have your chest cut open with a saw, and your blood circulate outside your body to be filled with oxygen to access the heart and bypass a blocked artery? Could a well-placed balloon catheter, in the hands of a talented Interventional Cardiologist (a new term that has entered the lexicon of patients and those treating the heart), achieve the same outcome? Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty might be a powerful solution to clearing a blocked single artery and regaining heart health. This procedure began to move patients away from that sharp scalpel in the eager hands of surgeons treating multi-vessel disease. The industry had entered an uncharted phase in treating coronary artery disease in Asia, and India would have a vital role in the process. Rajiv wanted to follow this trend as it would affect his sales of oxygenators.